Blackberry smoothy sauce. A 2-ingredient recipe, 100% foraged

This letter is the 5th episode of my 🔭 Laboratory Logbook, a monthly newsletter where I share my explorations.

For a few weeks now, for breakfast, I like to drink a large glass of self-picked wild blackberry juice. It’s a bit like swallowing a full jar of blackberry jam — without the refined sugar!

Without sugar, blackberry juice turns out to have a more subtle taste. But I like its intense dark purple. A concentrate of wilderness in my glass. It is just that, for some reason, I have been feeling like a slightly thicker texture. Something creamier, smoother, you know, a bit heartier.

So, I departed on a little adventure to develop a creamy blackberry sauce recipe for my — and your? — late summers…

I set myself 4 arbitrary rules in this experiment: (1) keep it raw, (2) target a simple 2-ingredient recipe, a duet, (3) only use plant-based ingredients foraged around me, and (4) keep as much of the subtle blackberry taste as possible.

In other words, I needed to find close by a wild thickener with a very mild taste. A friendly companion who would happily stay in the background, offering its reassuring hearty presence, gently letting the shy blackberry express its deep and subtle personality more assertively.

I think I have found an elegant wild friend for my blackberries!

But let me first tell you how I got there…

Table of Content

In search of a local and wild thickener!

Are purslane leaves a good thickener?

Purslane develops joyfully across our landscape, as a protective cover on disturbed and bare patches of dry soil hit by the powerful summer sun.

By curiosity, I try integrating purslane leaves into my blackberry sauce.

They bring a slight astringent greeny note competing with the blackberries, without thickening.

Not yet the magical ingredient I am looking for…

Mucilagenous lime tree leaves should work!

A few lime trees were planted along a nearby road. The slanted heart-shaped leaves with their silver fluffy back lead me to believe that they are Tilia tomentosa.

Last spring, while cooking lime tree leaves, I noticed their mucilaginous texture.

If I integrate them into my blackberry juice, they indeed thicken it. But their little hairs make the beverage fibrous and irritating for the throat.

Not exactly the smoothing thickener I am looking for! At least not this silver species, and not at the end of summer when leaves have become tougher.

Let’s turn to the vegetable garden: courgette?

After inspecting hedges and meadows around the house, looking for an appropriate wild edible, I resign myself to looking for a solution in my vegetable garden.

Courgettes! My only success this year in the garden.

They are sometimes used by raw cooks to thicken plant-based creams. Let’s try.

The courgette indeed thickens my blackberry juice. But its taste, although mild, overwhelms that of the blackberry.

It may pair well with strong-tasting foods, but it is not the discrete thickener I am looking for…

What about sweet potato leaves?

As I wander in despair in my garden in the heart of the drought, between my dehydrated potatoes and my lyophilized celery branches, I realize there is one vegetable that has been keeping growing under this tropical heat: sweet potato.

While fried in Taiwanese cuisine, sweet potato leaves reveal their mucilage. Let’s try.

It seems to work! When mixed in the blackberry juice, the sweet potato leaf remains quiet, leaving enough room for blackberry aromas. It also thickens the mixture. But, more towards some kind of slimy, viscous texture… You know, like a homemade yogurt that hasn’t set properly.

Too bad. We were almost there.

Let’s turn to ornamental hedges: rose mallow?

Keeping looking for a solution in the garden, starting to investigate ornamental plants in the hedges, I notice a rose mallow plant.

In these times of inflation, if you haven’t yet bitten into the rose mallow petals of your ornamental hedge, you should! They are a bit crunchy, with a mild flowery taste, a hazelnut note, and, an interesting mucilaginous texture.

Let’s add them to our blackberries.

I think we got it! The texture is thickened in an unctuous rather than viscous mode. The very soft fibers of the petals are indistinguishable to the throat. And their subtle aroma perfectly melts into that of the blackberries.

The only downside of rose mallow is that it is not the wild thickener I was looking for…

Looking for a wild candidate in the Malvaceae family: mallow flowers?

Yet, there are common wild cousins of rose mallow that were still flowering in nearby meadows about a month ago: mallows.

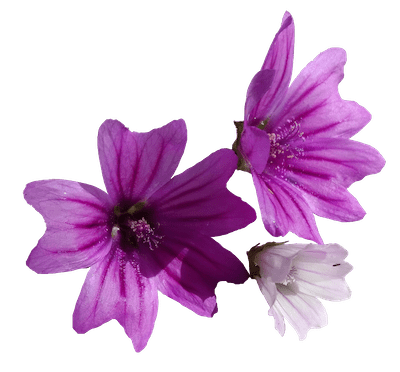

After checking again, I realize there still remain some little mallow plants here and there with their little mallow flowers. I find what I believe to be some common mallow, and some lighter and smaller dwarf mallow.

Let’s try!

Yes! Similar results as with rose mallow. Unctuous, not fibrous, mild taste. And, this time, 100% foraged ingredients!

If you are a botanist, you also concluded, like me, that the family of mallows — the Malvaceae — is a very good thickener candidate to be considered by wild chefs!

There are the common mallow, the dwarf mallow, rose mallow. But the lime tree precisely belongs to the Malvaceae! As well as the hibiscus, the very mucilaginous okra, and the marshmallow (Althaea officinalis) whose chewy mucilage used to be extracted to make the confectionery called marshmallow… It seems that Malvaceae’s mucilage has a structure close to that of pectin.

Eventually, in my little adventure in search of a wild thickener, I just ended up reinventing the wheel, or, should I say, reinventing the thickener!

It feels a bit sad to have lost so much knowledge about how everything we need is just growing as weeds, around us. But also joyful to see that during all this time, those treasures have been kindly waiting for us, on our doorstep. Next time I need to thicken a jam, a cream, a smoothie, a juice, a sauce, I will remember the Malvaceae family!

And just a last picture to show you how gracious mallow buds are, just before blooming:

The recipe (and variations) of blackberry and mallow smoothy sauce

Harvest blackberries and mallow flowers

For about 1 L of blackberries (4 cups), I use 1/3 L of flowers or 1/4 L if slightly compacted (1.3 cups, or 1 cup).

This proportion depends on which unctuousness you target, and how much you can actually collect. Even a few flowers will thicken to some extent.

I usually rinse the blackberries with filtered water a few times, to remove the dust and particles that tend to stick on them. You can keep only the petals of mallow flowers, or also include the calyx which is not very fibrous anyway but does contain mucilage.

You can use rose mallow flowers instead, or why not try hibiscus flowers if you have some at hand? I think sweet potato leaves may also produce an unctuous rather than viscous texture if used in smaller proportion, but I haven’t checked.

Extract the blackberry juice

I haven’t found yet a simple, pleasant, and efficient way to extract the juice.

The most straightforward is to use a juicer, but the seeds tended to accumulate and damage my juicer.

I discovered on this occasion that blackberry seeds are kind of little meteorites with tough shells.

Then, I tried to use a food mill. It works. If the blackberries are not too dry, we don’t need to pre-crush them. But we have to work bit by bit, regularly removing accumulated seeds. And we transform the counter into a mess.

I also tried to liquefy them using a blender or a mortar and pestle, and drain that paste using a cheese-cloth. It also works, but again, we need to work bit by bit, and we transform the counter into a mess.

Eventually, I am still looking for a better technique, but I continue to collect and extract the juice in one way or another, as I cannot resist drinking blackberry juice.

One liter of blackberries yields a bit less than half a liter of juice (4 cups yield ~1.8 cups).

Blend blackberry juice and mallow flowers

I haven’t tried another way than a blender, but in a stone mortar it might also work. After blending, you should already notice that the mixture is thicker.

Do we add something to enhance the flavors?

In order to enhance a bit the flavors, we could add a little bit of honey, a few drops of lemon juice, and even a grain of sea salt. But I usually prefer to keep it simple without adding anything. Also beware that honey or sugar may tend to liquefy the mixture by osmosis. Instead, I like to implement the following step to enhance the flavors…

Chill the mixture, for a few hours or overnight

I realized that chilling is important. It helps the mixture to develop more creaminess. It may even gel a little. But, more surprisingly, chilling enhances the blackberry flavor. Usually, the flavor of food is increased by warming up, but with blackberry I found that the opposite is true.

Top with one mallow flower

I think a delicate mallow flower on top of the sauce catches the eye and agreably balances the intimidating deep purple of blackberries!

And what to do with the residues of seeds and skins?

After juicing, we come up with tons of blackberry seeds. As our hens jump on cucumber juicing residues and welcome with gratitude celery juicing residues, I thought to offer them the blackberry residues. But they completely snubbed them.

I don’t put the seeds in the compost, afraid of spreading thorny blackberry bushes in the garden. I eventually sprinkle them in hedges along the road, precisely where blackberries don’t grow yet. Thus, I seed our creamy breakfasts for the years to come…

Bon appétit ;)

Lénaïc

Did you like this article?

Great! If you like recipes with few ingredients, you may like the lactofermented daikon radish recipe. If you like cooking foraged ingredients, you may like this article about how acorns have been prepared as food in History.